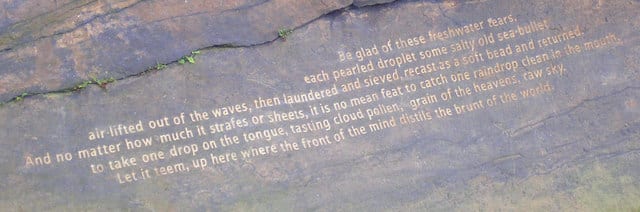

Image from the Stanza Stones project, a 50 mile upland walk from Marsden to Ilkley visiting the Stanza Stones carved with poems by Simon Armitage.

On the Poetry Book website Simon Armitage takes on the role of Sherlock Holmes for solving the mystery of the difference between poetry and prose. The Poetry Testing Kit offers ten guidelines for identification of a poem with the proviso it will never be an exact science. That’s ok. If it were, the magic would be lost and the mystery is part of the gestalt of the poetic form.

These guidelines are useful indicators for developing the necessary skills to turn plain words into something really special.

The Eye Test – How does it look on the page? Has some thought gone into its shape? Does the form bear some resemblance to the content?

The Magic Eye Test – If you look for long enough into the poem, will it reveal another meaning or picture hidden within it? Will further readings uncover further meanings and new rewards, and so on?

The Hearing Test – How does it sound? Read it out loud – does it work on the ear in some way?

The pH Test – A test for Poetic Handicraft. Does the poem use recognisable poetic techniques, of which there are hundreds? Are the techniques subtle, or do they poke out at the edge?

The IQ Test – Not a test for Intelligence Quotient, although that might come into it, but a double test for Imaginative Quality and Inherent Quotability: does the poem have some sort of dream life you can respond to: does it have lines or phrases that might stick in the memory?

The Test of Time – Would the poem outlive its immediate circumstances? This doesn’t mean it has to be ‘classic’ or ‘great’ or have some eternal message – it might just be a case of the poem withstanding a second reading. Remember, good poems can create their own contexts, and have poetic value way beyond their apparent shelf-life or sell-by date.

The Test of Nerves – Somebody once said that a poem shouldn’t just tell you not to play with matches, it should burn your fingers. In other words, does the poem create a sensation, rather than simply an understanding?

The Lie Detector Test – Poems don’t have to tell the truth, but they have to be true to themselves, even if they’re telling a lie. Give the poem a thump – does it ring true?

The Spelling Test – Does the poem cast a kind of spell or charm? At the very least does it create a world, even just a small but distinct world, capable of sustaining human life; a world whose atmosphere we can breathe and whose landscape we can inhabit for the duration of the poem?

The Acid Test – This is the final test and the one that really counts. It’s like a test for the mystery ingredient that separates a truly great tomato sauce from its rivals. It’s the X-factor, although it might be to do with the author’s experience of poetry. Is it possible to write a good poem if you’ve never read one? Somehow I doubt it.